Ontario Animal Health Network (OAHN) Public Health Update 2025

What is the OAHN Public Health Update?

The Ontario Animal Health Network (OAHN) was created to achieve coordinated preparedness, early detection, and response to animal disease in Ontario. OAHN is a “network of networks” with individual networks for different species/sectors, each of which involves collaboration among veterinarians, animal owners and stakeholders in the field with laboratory, academic and government experts. This annual update was created especially for public health professionals in Ontario, to highlight pertinent topics from the last 12 months from the OAHN companion animal and other species networks, to help strengthen the link and communication between animal health and public health networks.

The Ontario Animal Health Network (OAHN) was created to achieve coordinated preparedness, early detection, and response to animal disease in Ontario. OAHN is a “network of networks” with individual networks for different species/sectors, each of which involves collaboration among veterinarians, animal owners and stakeholders in the field with laboratory, academic and government experts. This annual update was created especially for public health professionals in Ontario, to highlight pertinent topics from the last 12 months from the OAHN companion animal and other species networks, to help strengthen the link and communication between animal health and public health networks.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever: Long Point ON (S2 2025)

At least 8 confirmed cases of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (Rickettsia rickettsii) in dogs and 2 cases in people who visited Long Point ON over the summer have been detected.

Results of recent tick dragging to confirm infection in local ticks are expected any time. It is difficult to predict how fast this pathogen could spread in Ontario given the wide distribution of the presumed vector here, Dermacentor variabilis. As of September, 32% of OAHN veterinary clinical impressions survey respondents were actively asking clients about travel to this area, but 27% were not yet aware of the outbreak.

Tick checks are especially crucial because the pathogen transmits relatively quickly once ticks attach, so common tick preventatives may not provide effective protection.

H5N1 influenza: Still here (S2 2025)

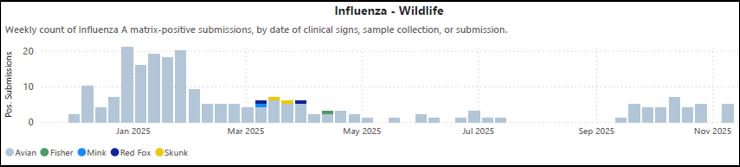

Although it was a relatively quiet summer in Ontario with regard to H5N1 influenza, activity increased significantly across Canada as the fall bird migration got underway. As of the end of November, numerous wild birds (see graph below), one raccoon, and at least six domestic poultry premises in Ontario have been affected this fall. Fortunately, the virus has yet to be detected in any dairy herds outside of the continental US, and no trace of the virus has been found in over 5600 samples of raw milk from 2700 dairy farms across Canada. Case reports of severe illness due to H5N1 influenza infection in cats continue to trickle in from the US as well, particularly associated with consumption of raw milk or raw meat-based diets (including commercial raw diets).

Companion animal veterinarians must maintain vigilance for this virus, particularly in cats that are acutely ill and have potential direct or indirect contact with infected animals or potentially contaminated products. It is important to promote testing in these patients, but this must generally be done at the pet owner’s expense. Veterinarians can make use of the NEW! OAHN guide to Influenza A diagnostic testing in Ontario for cats, dogs and exotics. Limited surveillance testing is also available for eligible cats (including barn cats and other outdoor cats) through the OAHN AIV in feral cats surveillance project, in partnership with the Canadian Wildlife Health Cooperative.

Advice for Ontario veterinarians:

- Encourage owners to avoid contact between pets and potentially infected wildlife (especially birds)

- Ask screening questions for sick pets

- Outdoor / wild bird exposure

- Raw milk / raw diet exposure

- Reinforce routine precautions for potentially infectious patients (i.e. gloves, lab coat, hand hygiene, segregation)

- Use enhanced precautions in suspect cases

- N95 respirator, face/eye protection

- Promote testing in suspect cases

- Testing is at the animal owner’s expense

- If diagnosis is unknown, use appropriate infection control measures as a precaution

Swine: Influenza A in pigs (S2 2025)

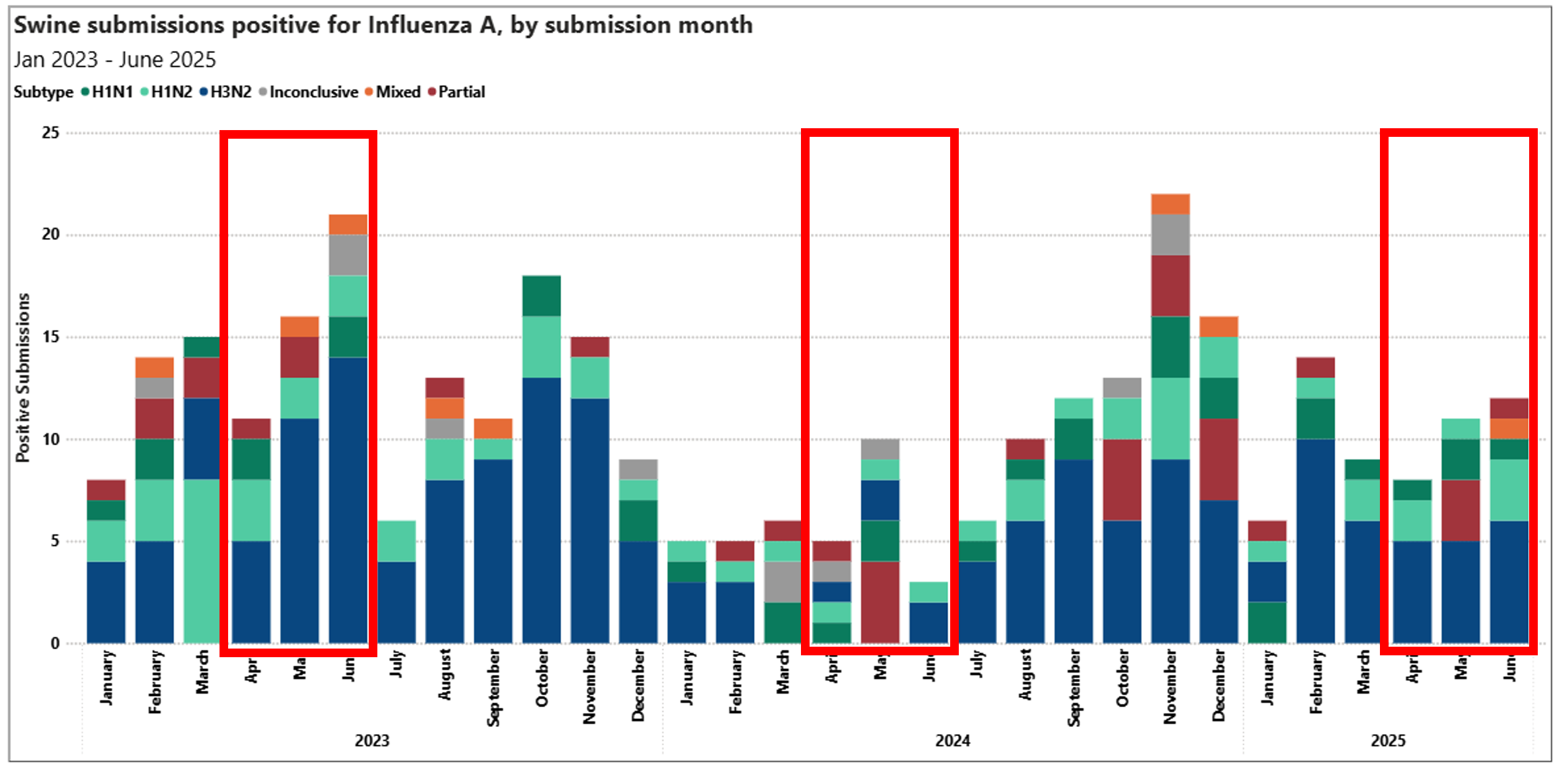

Influenza A virus (IAV) is a routine finding in farmed pigs. All detections of IAV in swine at the AHL in Guelph are tracked, sub-typed, sequenced and analyzed quarterly. Below is a graph showing the monthly detections and variant typing over the last three years, with boxes highlighting Q2 of each year. Each quarter these results are discussed by the OAHN Swine Network team. In Q2 2025, there were 31 positive cases, which was higher that 2024, but lower than 2023. Over half of the positive detections in Q2 2025 were H3N2, and there was one mixed isolation (H3N2 and H1N1 in the same sample). Most cases this quarter were in grower-finisher pigs (4-6 months old).

Most infections of IAV in swine are passed to the pigs from the people that care for them. It is very important to try to prevent spread of IAV (including H5N1) between people, pigs and birds to decrease the risk of genetic reassortments of the virus. The OAHN swine network routinely reminds all swine veterinarians, producers and smallholder producers to exercise enhanced biosecurity measures to keep diseases like IAV (including H5N1) out of pig farms:

- Preventing pigs from drinking untreated surface water

- Ensuring pig housing area (e.g. barns) are bird-proofed

- Deterring / excluding scavenger wildlife, including good deadstock management

- Not feeding unpasteurized milk / milk by-products to swine

- Evaluating risks from dairy and avian operations e.g. shared workers / equipment, proximity, etc.

- Encouraging workers to stay home whenever possible if sick

- Using extra precautions when working with sick pigs (e.g. N95 mask, diligent hand hygiene)

- Encouraging personnel who work with pigs to get their annual seasonal flu shot

Ontario Lepto trends, 2023-2024 (S1 2025)

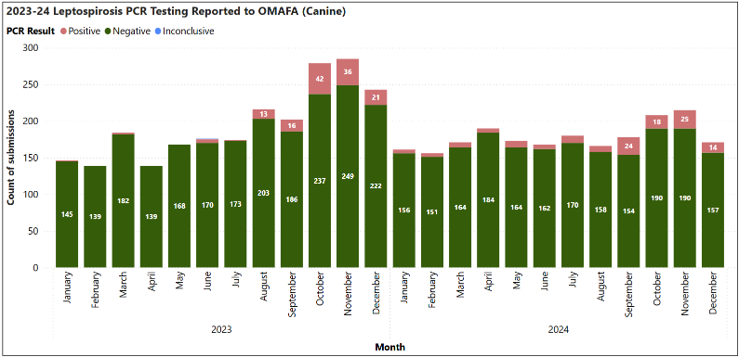

The latest update to the AAHA canine vaccination guidelines now lists leptospirosis vaccine as a core vaccine for most dogs, which is also consistent with the recently updated ACVIM consensus statement on leptospirosis in dogs. While the need for vaccination used to be based on a dog’s lifestyle and likelihood of exposure, nowadays even urban dogs with relatively limited outdoor access are not uncommonly affected by this very serious disease, due to its prevalence in periurban wildlife and in the environment in endemic regions like southern Ontario.

Leptospirosis still tends to follow traditional seasonal trends, with cases being most common during cool wet weather (e.g. in the fall) which favours environmental persistence of the organism in urine-contaminated water. This can also be seen in the graph below of lepto PCR test results by month over the last two years, as submitted to OMAFA by Ontario veterinary diagnostic laboratories.

Nasty & noteworthy parasites (S2 2025)

A dog in Oxford county developed spontaneous pneumothorax that was found to have been caused by infection with the lung fluke, Paragonimus kellicotti. A small number of such cases was detected in Ontario in 2021-2022 (check out the OAHN infosheet on P. kellicotti), but infection appears to be very uncommon in clinically normal animals. An additional 30-some healthy dogs on the same property, all with outdoor lifestyles and potential exposure to small prey, were screened for lung flukes and were all negative, but testing did detect one dog shedding Echinococcus multilocularis (EM).

An unusual case of EM was also detected in Niagara in a clinically normal 10-week-old kitten. Cats are known but very uncommon definitive hosts for this parasite compared to dogs and wild canids. The kitten was tested as part of a routine check up after being acquired through Kijiji, but it is presumed the kitten was from the same region, which is one of the higher risk areas for EM in Ontario.

One more nasty parasite for which veterinarians need to be on the lookout is New World Screwworm (NWS, Cochliomyia hominivorax). After being eradicated from the southern US and Mexico decades ago, this parasite is once again nearing the US border. Although there is currently no risk of the parasite establishing itself further north due to climate, it is important to identify in imported / travelling animals, as the maggots destroy living tissue and can cause significant damage. It is also critical to alert authorities at the pet’s point of origin if it came from a non-endemic area in the south.

Salmonella in people: Dog food / treats link (S2 2025)

The Public Health Agency of Canada recently posted a notice about an ongoing investigation into salmonellosis cases in people linked to handling of dog food and treats. Since February 2025, there have been 27 confirmed cases of a fairly specific strain of Salmonella Oranienburg across Canada, primarily out west but one case was found in Ontario. The report simply states that many people who became sick reported handling dog food or treats, including kibble, dehydrated and freeze-dried treats.

It may be difficult to pinpoint an exact source of the Salmonella in this outbreak, especially if there was contamination of batches of treats or food that have already been consumed.

This is an important reminder of the potential risks to people from handling these products – especially raw products, even if they have been preserved by various methods (check out the OAHN infosheet on RMBDs). Basic hand and household hygiene practices can protect pet owners from serious illness.

Other: Toxigenic C. diphtheria in donkey (S3 2024)

Routine culture samples from 35-year-old donkey with a history of chronic skin lesions on all four limbs yielded Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and, unexpectedly, Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Even more unexpectedly, the C. diphtheriae was positive on PCR for the diphtheria toxin gene. Toxigenic strains of this bacterium are reportable in humans, but are rarely detected (and therefore not reportable) in animals – this was the first isolation from an animal recorded at the AHL. Corynebacterium diptheriae is primarily a soil organism, so environmental exposure, along with immunocompromise related endocrine issues in this senior donkey, liklely accounts for this unexpected finding.

A related bacterium, C. ulcerans, is occasionally reported in livestock, and more recently in pets, and has potential for zoonotic spread to people. Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis (the cause of caseous lymphadenitis in small ruminants and pigeon fever in horses) in animals is periodically notifiable to OMAFA. These species can also carry the diphtheria toxin gene, but isolates from animals are rarely tested for it.

This case triggered a significant public health investigation, but ultimately the donkey was treated with antibiotics targeting Pseudomonas (more likely the primary pathogen), and there was no evidence of transmission to other animals or people in contact with the donkey.

Don’t-miss resources!

A study on rabies antibody titres in imported dogs, partly funded by OAHN, is now available as an open access article (Belanger et al. ZPH 2025).

Bites from dogs and cats are a risk for rabies transmission and can happen anytime. Keep the OAHN Veterinary Guidance for Domestic Animal to Human Bites Flowchart handy so you always know what to do (and not do) when a pet bites

Update: Lyme disease infographic (S2 2025)

OAHN has once again updated its infographic for veterinarians on ticks and Lyme disease in Ontario with the latest risk area map for Ixodes spp. ticks from PHO. It also has quick tips on monitoring, screening, and when not to treat dogs. Also check out the OAHN tick checklist for pet owners!

US canine imports (S1 2025)

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) remains in contact with the US CDC regarding US canine importation rules, which were set to be updated again in spring 2025. No additional changes have been made (yet) to the rules that came into effect in August 2024.

Wildlife rabies update (S3 2024 – S2 2025)

Forty-nine rabid bats were detected in Ontario in August alone, with the total number for the year at a record-breaking 105 so far, but with a percent-positivity lower than in 2024. The tragic case of bat rabies in an Ontario resident last year has no doubt contributed to increased awareness of the risks from bats (which is good), but unfortunately has likely also contributed to excessive fear regarding the true risk of transmission from bats when there is no direct contact. OAHN has therefore produced a handy bat contact guide to help discern what is and is not a rabies risk (for pets and people) when it comes to bats. Almost ALL dogs and cats – even if currently vaccinated – require a rabies booster within 7 days of a bat exposure, unless the bat can be tested (and is negative) within this window.

NEVER put a live bat in the freezer. Contacts for humane euthanasia of bats (and other animals for rabies testing) can be found on the OAVT Rabies Response Program (RRP) website. Also check out the new 1-page OAHN N2K: Bats in Ontario for more facts and tips on being kind to bats!

The last case of raccoon variant rabies in Ontario was detected in 2023. The last case of fox variant rabies in southern Ontario was detected in 2018, but it remains endemic in the north. The MNR once again successfully completed its rabies baiting and control operations in southern Ontario. Assuming no new detections, next year control efforts will return to focusing on high-risk areas along the border with New York State. A rabid fox kit was detected in the Ottawa area this summer, but typing confirmed it was a bat strain of the virus – an important reminder that spillover infections of any strain can occur in any mammal.

The last case of fox-variant rabies detected in southern Ontario was in 2018; based on ongoing surveillance efforts, this has led to the publication of a paper detailing the over 70-year journey to eliminate fox variant rabies from the southern Ontario. That’s HUGE! However, five red foxes from across northern Ontario tested positive for rabies in early 2025. This highlights the ever-present risk of Arctic fox variant rabies in arctic and sub-arctic habitats in Canada, where it is endemic across the geographic range of Arctic foxes (which also overlaps with the range of red foxes). Two recent cases of translocation of rabid dogs from northern to southern regions of Canada – a dog moved from Sanikiluaq NU to Winnipeg, and a dog moved from Umiujaq QC to Montreal – also clearly illustrate how risks in one region can have wide-reaching effects.

Rabies response and control in Ontario is a joint effort involving the public, animal owners, veterinarians, animal and wildlife control organizations, public health units, the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness (OMAFA) and the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR). The MNR maintains an interactive Ontario rabies surveillance map and posts annual maps of rabies cases in Ontario (including bat and non-bat rabies cases) and details of all annual rabies control operations.

REMEMBER: Owners who have a concern about potential exposure of one of their animals to rabies should always be referred to their local veterinarian FIRST. Additional detailed rabies response information for veterinarians is available on the Ontario Rabies: information for veterinarians page.

Parvo outbreaks: Windsor, London (S3 2024)

In December 2024, OAHN sent out an update about a large parvo outbreak at a housing complex in Windsor ON. It was reported at the time that a number of infected dogs had initially tested negative on point-of-care tests, but were later confirmed positive on PCR. This was similar to what happened during a parvo outbreak in Michigan in 2022. OAHN also provided a Need-2-Know factsheet on parvovirus tailored to dog owners in this and similar communities, with an emphasis on prevention, control and vaccination.

A similar cluster of parvo cases in a housing complex in London ON also made headlines in June 2025. A number of organizations worked together to organize vaccination clinics for the dogs living at the complex to try to stem the tide of cases.

Unvaccinated dogs are highly susceptible to parvovirus infection, and illness can be very severe and not uncommonly fatal, especially in young dogs. Vaccination is extremely effective at preventing illness, but it needs to be timed correctly. Although parvovirus is not transmissible to people, clusters of cases like this can be significantly influenced by and have dramatic effects on “people factors” which illustrate the effects from a One Health standpoint. Examples include socio-economic status affecting access to veterinary care, vaccine hesitancy affecting canine vaccination rates, and significant mental health impacts on individual owners, communities as a whole, and even veterinary staff trying to treat these tragic and all-too-preventable cases.

IN THIS ISSUE

- What is the OAHN Public Health Update?

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever: Long Point ON (S2 2025)

- H5N1 influenza: Still here (S2 2025)

- Swine: Influenza A in pigs (S2 2025)

- Ontario Lepto trends, 2023-2024 (S1 2025)

- Nasty & noteworthy parasites (S2 2025)

- Salmonella in people: Dog food / treats link (S2 2025)

- Other: Toxigenic C. diphtheria in donkey (S3 2024)

- Don’t-miss resources!

- Update: Lyme disease infographic (S2 2025)

- US canine imports (S1 2025)

- Wildlife rabies update (S3 2024 – S2 2025)

- Parvo outbreaks: Windsor, London (S3 2024)

USEFUL LINKS

Companion Animal NETWORK TEAM:

- Eastern ON: Dr. Julie Calvert

- Southern ON: Dr. Emma Webster

- Northern ON: Dr. Hailey Bertrand

- GTA ON Dr. Donia Eino

- Animal Health Lab: Dr. Kris Ruotsalo Dr. Emily Brouwer

- Ontario Vet College: Dr. Scott Weese Dr. Allison Collier

- OMAFA: Dr. Maureen Anderson Dr. Bukunmi Odebunmi

- Network coordinator: Dr. Tanya Rossi