Ontario Animal Health Network (OAHN) Bovine Expert Network Quarterly Producer Report

OAHN Q4 Bovine Animal Health Laboratory Data

There were 214 bovine pathology submission between November 1st, 2020 and January 31st, 2021.

Salmonella

In total, bacterial culture isolated Salmonella spp. from 17 submissions this quarter, representing an estimated 15 unique premises. Salmonella Dublin was the isolate in 8 of these cases, representing an estimated 6 premises, similar to Q3. The primary finding associated with isolation of S. Dublin was septicemia with concurrent pneumonia. Other isolates included S. infantis (septicemia, pneumonia), S. Heidelberg (septicemia with concurrent viral enterocolitis in a young calf), S. Typhimurium var Copenhagen (necrotizing enteritis in a young calf), and S. enterica (diarrhea in an adult animal).

Respiratory disease

As seen in Q3, pneumonia was the most frequent pathology diagnosis in cattle over 2 months of age (n=24). The most common pneumonia etiologies detected in young cattle this quarter were Histophilus somni (n=12), BRSV (n=11), Mannheimia hemolytica (n=7), Pastuerella multocida (n=7), and Mycoplasma bovis (n=6).

M. haemolytica was often identified along with P. multocida and/or Mycoplasma bovis, and a few cases had concurrent Histophilus somni and Pasteruella multocida infection. Several cases had H. somni or BRSV identified as the sole agent identified. M. haemolytica was the dominant etiology for pneumonia in mature cattle this quarter, and one case had concurrent isolation of P. multocida and Bibersteinia spp.

Enteric disease

Of the 24 submissions with a diagnosis of enteritis in young calves, the dominant infectious causes were rotavirus (n=17), cryptosporidium (n=12) and coronavirus (n=7), with concurrent infections identified in several instances. Two cases of enteritis were identified in older calves, with one attributed to coccidiosis and the other to BVDV infection.

Abortion

There were 19 submissions for abortion investigations (dairy n=13, beef n=4, commodity not reported n=2). The infectious causes of abortion identified were bacterial (n=5, including Trueperella pyogenes and E. coli), Leptospirosis (n=2), Neospora (n=1).

Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus

A total of 92 submissions included BVD testing. Of the 276 PCR tests performed, 4 were positive. Of these, 4 were identified as part of herd screening, and 1 was identified in association with a case of bronchopneumonia. Additionally, one positive case was identified by immunohistochemistry as the cause of necrotizing enteritis in a beef calf that had concurrent bronchopneumonia.

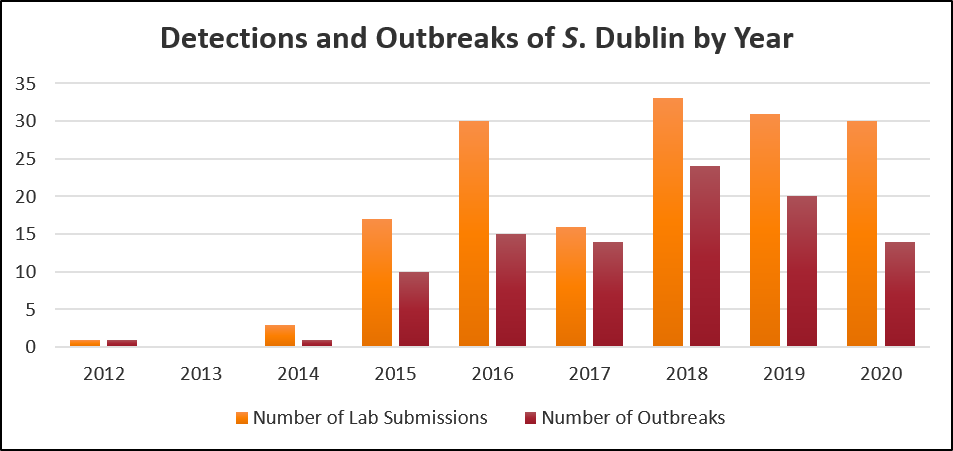

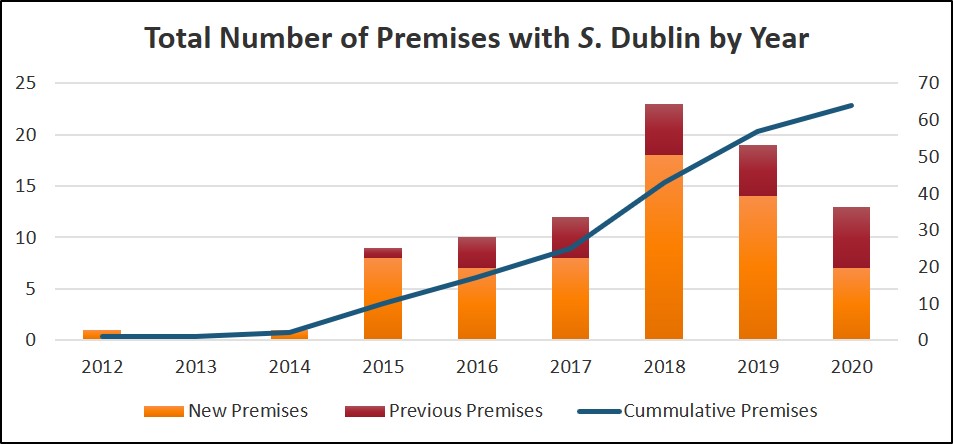

2020 Salmonella Dublin Update

Salmonella Dublin is an emerging disease in Ontario. Laboratory submissions where Salmonella Dublin was isolated on bacterial culture are regularly monitored and reported by the OAHN bovine network.

During 2020, 30 submissions to the AHL detected Salmonella Dublin. Among these submissions:

- 28 detections were on tissue samples collected at postmortem and 2 detections were fecal samples

- 29 detections were from calves and 1 detection was from an aborted fetus

In some cases, more than one sample was submitted from the same farm during a diagnostic investigation. The submissions are estimated to represent 14 separate outbreaks from 13 different farms. For seven farms, this was their first diagnosis of S. Dublin. As of December 31, 2020, it is estimated that 64 unique premises have had Salmonella Dublin detected, of which 31 are veal, 32 are dairy, and 1 is a beef operation.

OAHN Mastitis Report

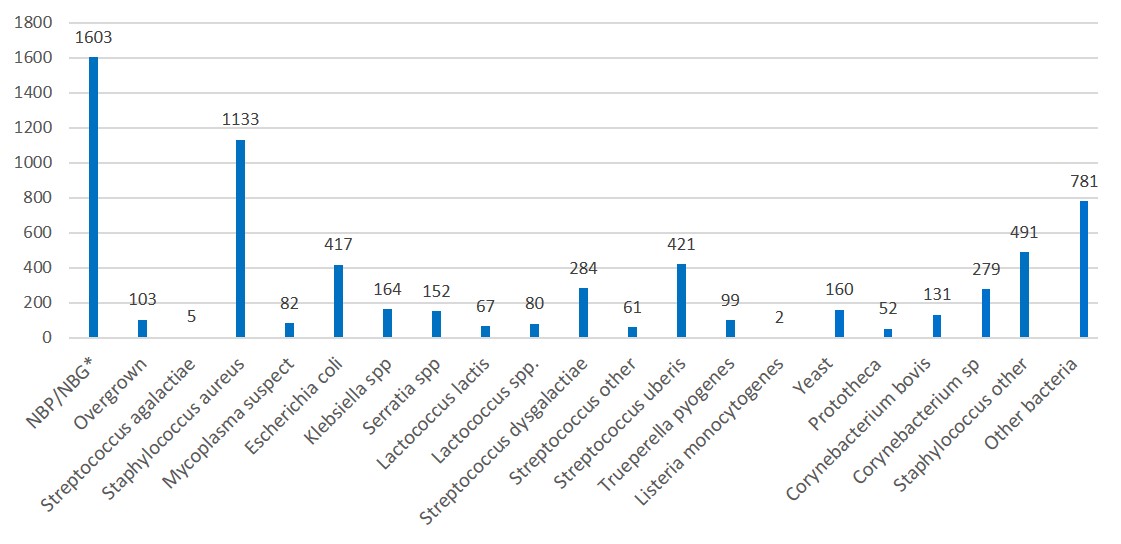

Mastitis Pathogens from Milk Cultures Submitted to the Animal Health Laboratory in 2020

Summary provided by Dr. Durda Slavic and Dr. Murray Hazlett

In 2020, there were 5,326 individual milk samples sent to the AHL which yielded 6,567 results.

Mastitis PCR Test Data for Ontario Lactanet Herds in 2020

Summary provided by Dr. David Kelton, OVC in collaboration with Lactanet

- While 17% of samples were positive for Staph aureus, less than 7% were HIGH positive

- For Staph aureus cows, SCC is correlated with PCR result (as expected)

- Caution: Low positive Staph aureus tests might not be infected – check SCC

- Only 1 of 10,771 samples positive for Strep ag (eradicated!)

OAHN Project Summary: Parasitism in Cattle

Dr. Jessica Gordon, Ontario Veterinary College

In 2019, OAHN supported submissions of fecal samples for fecal egg counts (FEC) of eggs from gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) species. The eggs from GIN (aka roundoworms) are indistinguishable under a microscope, so FEC group them into overall count for GIN species. How likely a roundworm is to cause disease varies by type. The most common roundworms in cattle in Canada are Ostertagia ostertagi, Cooperia oncophora and punctata, and Nematodirus helvetianus. Roundworms are transmitted between cattle on pasture, when eggs laid by mature worms in the gut of infected cattle are excreted in the feces. These eggs hatch in the environment and mature to L3 larvae, which are infective if eaten. Pasture is required for transmission, so cattle housed entirely indoors will not become parasitized.

Project Results

During the OAHN project, 100 samples were submitted from 54 owners across Ontario. Forty samples were from dairy farms, 59 samples were from beef farms, and 1 sample was not identified. The range of animal ages represented was calves to mature cows, but for about 2/3 of the samples the age of the animals sampled could not be determined. Fecal egg counts ranged from 0 epg to 102 epg for GIN species. Ten samples contained no GIN eggs and 25% were above 20 epg. Coccidia was also present in 50% of beef samples and 75% of dairy samples.

The plan with this project was to target farms with high FEC for more in-depth data collection. Unfortunately, due to the timing of the initial sample collection this could not be completed in 2019 and was impossible to do in 2020 due to COVID restrictions. Though we did not gather all the data we hoped to in this study, there is still some important information that can be gleaned from the results.

Overall, the FEC for roundworms is relatively low across Ontario. The exact FEC that results in economically important reduction in production in cattle has not been well established, but we generally think of anything <20 epg as being low. Of all the samples submitted, only 25% were greater than 20 epg. This value was similar for both beef and dairy, with 27.5% of dairy samples and 25% of beef samples >20 epg. The exact epg guideline used varies based on the age of the animal and management conditions. Consult your veterinarian to determine what your FEC results mean for your herd.

There was no connection between previous dewormer use and GIN counts at the time of sample submission. This piece is tricky to interpret because the time between treatment and sample collection varied from ~1-10 months. As most roundworms have a prepatent period (time between ingestion of L3 on pasture and presence of eggs in feces) of 15-21 days, if the cattle were on pasture after treatment, all cattle sampled had time to be reinfected before sample collection.

The most appropriate way test the efficacy of dewormers is using a fecal egg count reduction test (FECRT). To do this, you take fecal samples from animals in the herd, submit them for FEC, and treat the animals with the anthelmintic(s) in question. It is important to be as accurate as possible when dosing animals to get a true idea of how well the anthelmintic is working, so use of a scale is recommended. You then take fecal samples about 14 days after treatment for a repeat FEC. If an anthelmintic is effective, you expect to see a 90-95% reduction in FEC between the first and second samples. FECRT are most accurate if done at the peak of FEC, which would be late July-early August in Ontario cattle. Work with your veterinarian to determine the most appropriate protocol for a FECRT on your farm.

Though it does not tell you the effectiveness of a dewormer, looking at the FEC in late July-early August would give you an idea about the need to deworm your cattle. You can do this by taking samples from fresh fecal pats in the pasture. Your veterinarian can help you determine the best way to sample your cattle and how to interpret the results. If your herd is quite high or remains high for multiple years, it is time to invest in a FECRT, even given the increased effort.

As we continue to learn more about roundworms and dewormer resistance in cattle, deworming recommendations will likely change. For now, it is important to understand the concept of refugia (Figure 1). Refugia means do not deworm all animals so some parasites are not exposed to a dewormer. This is generally done through targeted deworming, or only deworming a portion of the herd. Speak with your veterinarian regarding recommendations for targeted deworming on your farm. Leaving some susceptible parasites in the animals means pastures are populated with both susceptible and resistant eggs and infective larvae. Thus, the parasites animals pick up in the environment include both susceptible and resistant parasites and dewormer use has a chance of success in animals that require treatment.

Understanding the level of parasitism on your farm can help you and your veterinarian develop appropriate roundworm control programs. If you also have results of a FECRT, recommendations can be tailored to ensure the dewormers you use are working and decrease the use of unnecessary dewormers. This can not only save time and money, it will also help ensure that dewormers continue to work in animals that require deworming to protect their health.

LAST CALL for Submissions to the OAHN Project

Disease testing in newly introduced cattle

The OAHN project that provides a panel of tests for newly or recently purchased dairy and beef cattle will close April 30, 2021. Eligible cattle are tested for Salmonella Dublin, Johne’s, Bovine Leukosis Virus, and Anaplasmosis. Results are delivered directly back to the submitting veterinarian.

For more information on the project, visit the OAHN website project page here.

To participate, contact your herd veterinarian.