Ontario Animal Health Network (OAHN)

Equine Expert Network

Quarterly Veterinary Report

Read about our OAHN Equine ACTH project!

“Investigation into the seasonal variations in ACTH levels in Ontario’s senior horses (aged 15 years+)”

BITS ‘N SNIPS (or “things we talked about on the network call”)

Chewing Lice (Werneckiella equi)

There were a number of references to “lice” as an increasing problem this quarter with several horses on a farm affected . The source of the infections were not easily identified.

Lice spend their entire life cycle on the horse. A female lives for 30-35 days and deposits 1 egg/day. The eggs hatch in 5-20 days into nymphs. The lice breed in the hair coat, and winter coats make for a particularly welcoming habitat . The lice feed on dead skin cells, hair and secretions. Lice are transmitted directly between horses or indirectly by fomites (e.g. grooming equipment, fence posts.). The lice can only live for a couple of days off of the host.

Clinical signs: Pruritis, skin irritation, rough coat., nervous attitude. Chewing lice are found most commonly on the head, mane, tail base, shoulders, trunk.. The eggs are white and are “glued” to the hair shafts. Chewing lice move quickly.

Treatment: There are no available dusts for horses anymore. For horses, the only approved products are sprays or wipe-ons and the products must reach the skin. Many people will clip their horses prior to application but this must be done in light of the horse’s management. Oral ivermectin does not work as well for chewing lice as it does for sucking lice. All fomites should be washed and treated with an effective insecticide.

Most insecticides kill adults and nymphs but not eggs and therefor a second treatment 14-21 days after the first is necessary. Some veterinarians will recommend treatments three times, 10 days apart. Some horses will react to the products with skin sensitivity (itchiness, hair discolouration).

If weather permits, horses can be bathed in a insecticide-based shampoo.

Recently, essential oils , namely tea tree or lavender oil have been shown to decrease louse populations in donkeys (and people). Essential oils in the management of the donkey louse, Bovicola ocellatus

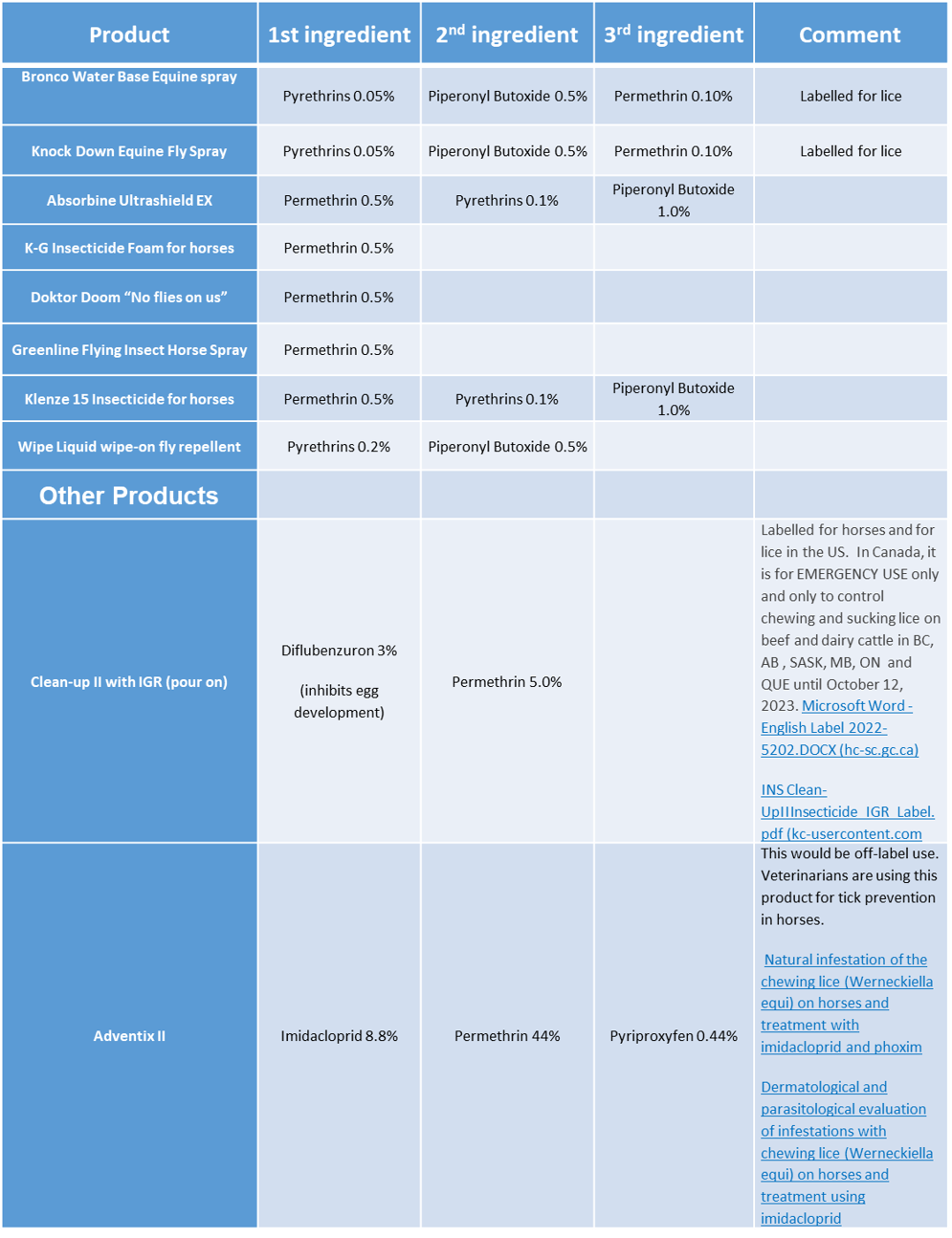

Below is a list of products registered in Canada that would be effective against lice when used appropriately. Only two are labelled for lice treatment and are only for nymphs/adults.

To look up the ingredients in an insecticide spray please go to the Pest Management Regulatory Agency label search here.

Ergot alkaloid toxicity

After a Standardbred breeder lost 4 foals, one from abortion and three due to dystocia from malpresentation, he began his own investigation into a potential cause. He was suspicious of the hay as this was the first year they had baled their own hay from the paddocks. They had been feeding that hay since late fall/early winter. The first abortion occurred in January and then the dystocias began in late February/early March. One of the next mares due to foal also had placental edema on ultrasound examination. Although not what veterinarians consider the typical presentation for “fescue toxicity” (prolonged gestation, agalactia), the breeder was concerned and sent hay and straw samples for ergot alkaloid testing. The results: 387.4 ppb in straw and 50 ppb in hay. Foaling issues can be experienced with ergot alkaloid levels as low as 20 ppm. The breeder replaced the straw and hay and had no more issues.

Ergotism is caused by the endophytic fungus Claviceps purpurea which lives on a variety of hays and pasture grasses. The main alkaloids produced are: ergotamine, ergostine, ergocristine, ergoryptine and ergocornine.1 Mares are sensitive to ergot alkaloids, affected by concentrations as low as 20-100ppm, compared to cattle (1000-2000ppm).1 The alkaloids suppress serum prolactin and progestagens causing a prolonged gestation, agalactia and a thickened edematous placenta. Foals are born small, weak or stillborn. Dr. Bob Wright et al. reported a case of ergotism in a group of late-gestation mares in Ontario caused by consumption of cereal rye straw bedding.2 The mares foaled around their normal due date but had signs typical of fescue toxicity. Of the 8 mares to foal, 7 had dead foals. There are several management recommendations listed here, but because most of the endocrine effects of ergot alkaloid exposure occurs after day 300 of gestation, removal of pregnant broodmares from sources of ergot alkaloids at least 30 days before expected foaling has been successful.3

In 2022, several farms across Ontario with varying species (cattle, small ruminants) had animals displaying clinical signs of ergotism.

Testing forages for ergot alkaloid can be done at a variety of laboratories, some of which are listed below:

Mycotoxins – Actlabs (Ontario)

Ergot – Dairyland Laboratories, Inc. (dairylandlabs.com)

Sample Collection Guidelines for Ergovaline Testing | University of Kentucky Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (uky.edu)

Ergot Alkaloids by LC/MS/MS Screen – NDSU VDL

- Ergot alkaloid (ergopeptine) toxicity in horse hay and pasture | ontario.ca

- Wright RG, Boyce B, Van Dreumel T, Hazlett MJ, Cross DL. Ergot alkaloid toxicity in foaling mares associated with eating cereal rye straw. Abstract presented at Equine Nutrition and Physiology Symposium, Lexington KY May 28/01.

- Endocrine alterations associated with ergopeptine alkaloidexposure during equinepregnancy.Evans TJ.Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2002 Aug;18(2):371-8,

Other useful information:

Using On-Farm Monitoring of Ergovaline and Tall Fescue Composition for Horse Pasture Management.Lea KM, Smith SR.Toxins (Basel). 2021 Sep 25;13(10):683. Free PMC article.

Network Member Reports

| Southwestern Region

(Melissa McKee) |

Strangles cropping up quite regularly this quarter and boarders /horse owners have been taking it more seriously. Many barns are requiring a negative S. equi PCR on nasopharyngeal lavage. There was a case of EHM due to the non-neuropathic strain in an older horse, with a good vaccination status. He showed typical signs (ataxia, weak behind and urine dribbling) . We seem to have diagnosed more mares with placentitis than in other years, an abortion with a long umbilical cord, and one facility with ergot alkaloid toxicity. We have also seen several cases of lice this quarter. Vaccine reactions (fever, neck pain, mild colic) continue to occur particularly with the multivalent vaccines and rabies. (multi vaccines and rabies). We have had fewer reactions with separating the vaccines . Several horses returning from Florida had colic and some required fluid therapy. |

| Western Region

(Tara Foy) |

We had a number of farms dealing with lice this quarter. As well, a number of farms were dealing with foal diarrhea (we might have the KY strain of rotavirus Rotavirus Information Center | Gluck Equine Research Center (uky.edu)). We also saw a number of dystocias, periparturient emergencies and respiratory disease in foals |

| Eastern Ontario

(John Donovan) |

We had a few reproductive issues this quarter: one dystocia and one retained placenta in a mare that developed toxemia and subsequent laminitis We have had foals with failure of passive transfer, one with sepsis , one with a septic joint, one with contracted tendons, and one with a valgus angular limb deformity, This quarter we also saw a number of colics (impactions, in Jan and Feb and spasmodic colics in the last couple of weeks. We also saw a very interesting case of equine hiccups in a 3 year old Hanoverian filly who began training. Unilateral swelling of the larynx and Grade 3-4 gastric ulcers were diagnosed on endoscopy and the hiccups have resolved with ulcer treatment. We also saw an Increase in lice cases this quarter as well as Clyde itch in the heavy horses. We diagnosed two fractures in Jan/Feb: a hind cannon bone fracture and a P1 fracture. We are also seeing a lot of ticks, likely due to the mild winter. We continue to use large dog Advantix off –label. |

| Ontario Veterinary College

(Memo Arroyo) |

We saw a fair amount of Strangles cases this winter. We had a few lacerations as well as a a couple of foals with gastrocnemius rupture due to dystocia with general good prognosis . We had typical postpartum mares with hematomas, vulvovaginal tears and retained placentas. We haven’t had to perform many C-sections this quart and we don’t feel our dystocia caseload is increased over other years. Our total number of mares and foals admitted to the hospital is down. |

| AHL Pathology

(Emily Ratsep) |

|

| Alison Moore

(OMAFRA) |

Strangles became an immediately notifiable disease this quarter. We had 5 facilities affected in Oxford, Simcoe, Wellington, Grey, and Lanark Counties

We had two farms affected by EHM due to EHV-1 this quarter. Both farms were in Wellington County . Please follow Outbreaks | Equine Disease Communication Center (equinediseasecc.org) for reported outbreaks. |

Syndromic and AHL Laboratory Data Surveillance Dashboard

Survey – Key points

- 23 Counties represented

- 71% equine, 13% equine and food animal , and 8% equine and small animal clinics responded; the remainder were mixed animal and referral.

- Increase in (foal) colic, fever of unknown origin, septicemia, joint ill, wry nose and brachygnathia, hypothyroidism, ; (adult)

New conditions or those without a diagnosis:

- Bloody unilateral nasal discharge for 10 days with no findings on x-ray and scope. Persistent low WBC in a racehorse that is predictably linked to poor on-track performance, no other lab abnormalities, no improvement with treatment for EGUS or hindgut inflammation.

- Several cases of riding horses with blocking pattern that suggested high suspensory but on MRI we found significant lesions in the carpus instead.

- Recurrent abscesses at girth line on ventrum (horses are not ridden and do not wear any tack), They share a field but others in the field are not affected). Culture came back as Corynebacterium ulcerans. Cleared up with TMS and topical flushing/scrub but recurred two months later.

- 15 year old pregnant mare went down in her last 2 months of gestation. Unable to rise and died within 48 hours. Herpesvirus negative PCR on blood sample.

- Cystoliths : 3 horses (2 mares) without alfalfa diets

- Fever related to colic signs.

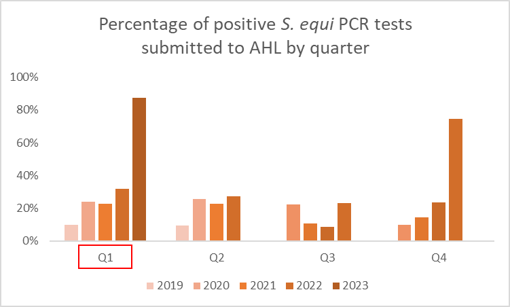

There was a significant increase in the percent of positive S. equi PCRs in Q1 2023 versus Q1 2022 . The reporting of S.equi positive results, repeated testing to identify carriers as well as testing prior to moving horses to new facilities are contributing to the increase in the percent of positive tests.

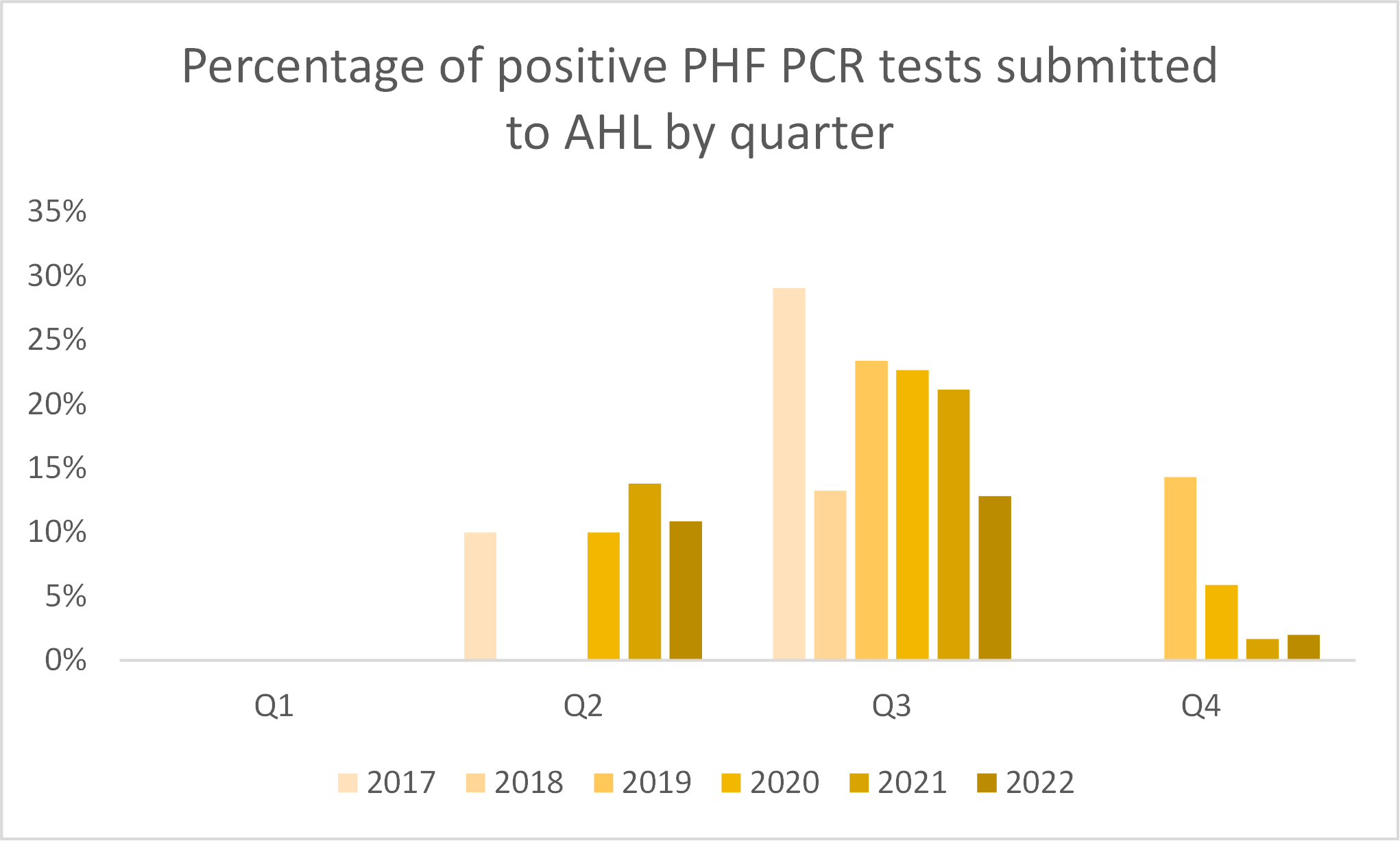

No positive test results for PHF occurred in Q1 which is typical for the disease.

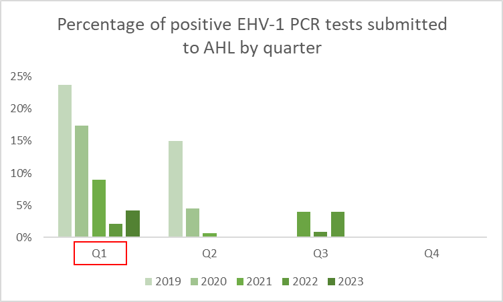

There were 8 positive tests for EHV-1 this quarter. Q1 is the most significant time for positive EHV-1 test results.

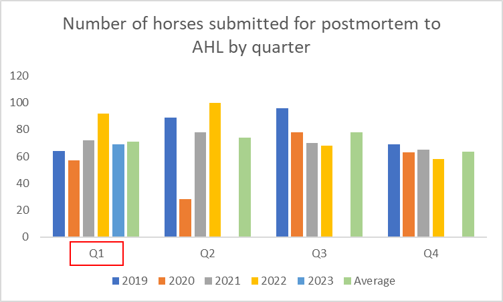

The number of horses submitted to AHL for postmortem in Q1 are slightly decreased to those of Q1 2022.

The number of nervous system diagnoses was significantly decreased compared to Q1 2022. Gastrointestinal , respiratory and musculoskeletal diagnoses were increased in Q1 compared to Q1 2022.

Equine research from Ontario and around the world

Researchers in Ontario

Direct and culture-enriched 16S rRNA sequencing of cecal content of healthy horses and horses with typhlocolitis.Zakia LS, et al. PLoS One. 2023. PMID: 37053174 Free PMC article.

Effects of concentrated fecal microbiota transplant on the equine fecal microbiota after antibiotic-induced dysbiosis.Di Pietro R, et al. Can J Vet Res. 2023. PMID: 37020579

Effect of dietary iron supplementation on the equine fecal microbiome.Arantes JA, et al. Can J Vet Res. 2023. PMID: 37020575

Plasma and Synovial Fluid Cell-Free DNA Concentrations Following Induction of Osteoarthritis in Horses.Panizzi L, et al. Animals (Basel). 2023. PMID: 36978592 Free PMC article.

Equine alveolar macrophages and monocyte-derived macrophages respond differently to an inflammatory stimulus.Kang H, et al. PLoS One. 2023. PMID: 36920969 Free PMC article.

Delayed embryonic development or a long sperm survival in two mares-A registration conundrum.McCue PM, et al. Equine Vet J. 2023. PMID: 36917554

Effect of plasma transfusion on serum amyloid A concentration in healthy neonatal foals and foals with failure of transfer of passive immunity.Palmisano M, et al. J Vet Intern Med. 2023. PMID: 36825688 Free PMC article.

The influence of a probiotic/prebiotic supplement on microbial and metabolic parameters of equine cecal fluid or fecal slurry in vitro.MacNicol JL, et al. J Anim Sci. 2023. PMID: 36715114

The Global Seroprevalence of Equine Brucellosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Based on Publications From 1990 to 2022.Jokar M, et al. J Equine Vet Sci. 2023. PMID: 36649828 Review.

Researchers around the world

Immunotherapy of Equine Sarcoids-From Early Approaches to Innovative Vaccines.Jindra C, et al. Vaccines (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37112681 Review. Free article

Equine Gram-Negative Oral Microbiota: An Antimicrobial Resistances Watcher?Pimenta J, et al. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37107153 Free article

Clinical Aspects of Bacterial Distribution and Antibiotic Resistance in the Reproductive System of Equids.Tyrnenopoulou P, et al. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37107026 Review. Free article

Social Box: A New Housing System Increases Social Interactions among Stallions. Zollinger A, et al. Animals (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37106974 Free article

Ultrasound Morphometry and Mean Echogenicity of Digital Flexor Tendons, Suspensory Ligament, and Accessory Ligament of Digital Deep Flexor Tendon in Gaited Horses.Schade J, et al. Animals (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37106973 Free article

Effect of pentobarbital as a euthanasia agent on equine in vitro embryo production.Martin-Pelaez S, et al. Theriogenology. 2023. PMID: 37084499

Guide to diagnosing and managing skin diseases in horses.Long S. Vet Rec. 2023. PMID: 37084195 Review.

Serum nerve growth factor in horses with osteoarthritis-associated lameness.Kendall A, et al. J Vet Intern Med. 2023. PMID: 37083137 Free article.

Changes in Calprotectin (S100A8-A9) and Aldolase in the Saliva of Horses with Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome.Muñoz-Prieto A, et al. Animals (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37106929. Free article

Risk Factors for Epistaxis in Thoroughbred Flat Races in Japan (2001-2020).Sugiyama F, et al. Animals (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37106911. Free article

Factors Affecting Weigh Tape Reading in the Measurement of Equine Body Weight.Grimwood K, et al. Animals (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37106893. Free article

Factors Affecting Thoroughbred Online Auction Prices in Non/Post-Racing Careers.Camp M, et al. Animals (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37106892 Free article

Homocysteine-Potential Novel Diagnostic Indicator of Health and Disease in Horses.Gołyński M, et al. Animals (Basel). 2023. PMID: 37106874 Review. Free article

Zinc Status of Horses and Ponies: Relevance of Health, Horse Type, Sex, Age, and Test Material.van Bömmel-Wegmann S, et al. Vet Sci. 2023. PMID: 37104450. Free article

A Systematic Review of Current Applications of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Horses.Tuniyazi M, et al. Vet Sci. 2023. PMID: 37104445 Review. Free article

Relationship between plasma dopamine concentration and temperament in horses.Kim J, et al. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2023. PMID: 370878

Interested in avian Influenza virus (AIV) in wildlife and pets?

The OAHN Wildlife network has two influenza projects on the go. The objective of one project is to determine which wild mammals can be infected with AIV and the prevalence of the virus in different species and, of the second project, to determine the detection of AIV in environmental water samples as an early warning system. Read about the projects here and here.

Visit the CFIA webpage “Pets and H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza” for information on how avian influenza may affect your pet.

ResearchONequine.ca is a website developed by the Ontario Animal Health Network equine network to help increase research awareness and to connect researchers from academia, industry and government with the ultimate goal of improving the lives of all equines. It was supported by OAHN and the Ontario Association of Equine Practitioners.

is a website developed by the Ontario Animal Health Network equine network to help increase research awareness and to connect researchers from academia, industry and government with the ultimate goal of improving the lives of all equines. It was supported by OAHN and the Ontario Association of Equine Practitioners.